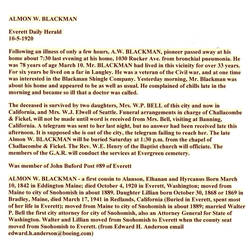

Almon W. Blackman

Representing: Union

G.A.R Post

- John Buford Post #89 Everett, Snohomish Co. WA

Unit History

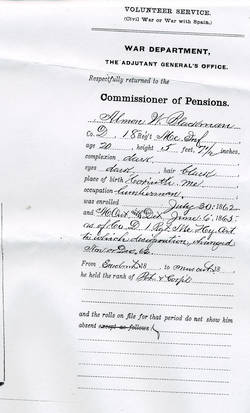

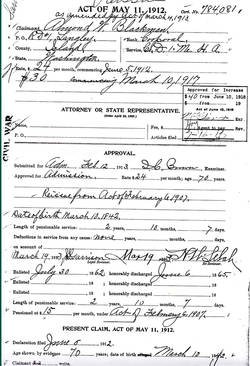

- 1st Maine Heavy Artillery D

- 18th Maine Infantry

Full Unit History

1st MAINE HEAVY ARTILLERY

Organized: August 1, 1862

Mustered Out: June 6 – Sept. 11, 1865

18th MAINE INFANTRY

Mustered In: August 21, 1862

Discharged: December 19, 1862

Transferred: Dec. 19, 1862 to 1st ME Heavy Artillery

Discharged: June 6, 1865

Highest Rank: Cpl.

Regimental History

REGIMENTAL HISTORY: (1st)

The change in designation from infantry to heavy artillery was due to the fact that this regiment trained in both infantry and heavy artillery tactics. The organization of the regiment was changed as well, as two new companies were added; increasing the number of companies from 10 to 12 and the size of each company was increased from 100 to 150 men, bringing the total strength of the regiment to 1800. The companies of the regiment, stationed in the defenses of Washington, building and garrisoning batteries and forts, had escaped the hardships and struggles of battles such as Antietam, Chancellorsville and Gettysburg. In the spring of 1864 with a shift in strategy in the Union command life would dramatically and profoundly change for the men of the First Maine Heavy Artillery.

In the spring of 1864 Union General Ulysses S. Grant launched his Overland Campaign against the Confederate Army of Robert E. Lee in hopes of ending the war once and for all, after convincing Secretary of War Edwin Stanton and President Abraham Lincoln that he needed to get all available troops into the field. For the First Maine Heavy Artillery the request meant that they would leave the relative comfort and safety of garrison duty and join their comrades in the field for the final push on to Richmond. On May 14, 1864 the First Maine Heavy Artillery, along with several other heavy artillery regiments, was ordered to organize as a separate division under the command of Brigadier General Robert O. Tyler. Tyler’s Division of Heavy Artillery was then ordered to the front to join Grant’s Army of the Potomac as part of the Union Army’s Second Corps under the command of Winfield Scott Hancock.

After 2 ½ years protecting Washington the First Maine was on the way to the front lines. On May 15, 1864 the First Maine Heavy Artillery regiment was transported down the Potomac, and joined the Army of the Potomac at Belle Plain Landing Virginia. It was shortly after the bitter fighting at the Wilderness and Spotsylvania, and the First Maine Heavy Artillery Regiment, at full strength was a stark contrast to many of the veteran regiments which had suffered devastating losses on the front lines. The size of the First Maine made it larger than most front line brigades, which had been worn down by months of casualties.

On May 17th the First Maine left Belle Plain and marched to the City of Fredericksburg where it crossed the Rappahannock River and began to hear the roar of guns in the distance. Upon arriving at the front on the morning of the 18th of May the Heavy Artillery Regiments, fresh and at full strength, began to see the results of war. The view of the battlefield was not a pleasant sight to behold as there were dead and wounded soldiers from both sides, some in small groups, others laid out individually across the battlefield.

After being briefly under fire on May 18th, the men of the First Maine spent the first part of the day on the 19th encamped in a wooded grove near an open field off the Fredericksburg Pike outside of Spotsylvania Court House. Encamped along with other freshly arrived Heavy Artillery regiments of General Robert O. Tyler’s 4th Division of the Second Army Corps, the First Maine found themselves holding the rear right flank of the Union Army. The Union Army was beginning to disengage from the lines around Spotsylvania Virginia, and was preparing to move south towards Richmond in an all out attempt to outflank Confederate General Robert E. Lee and his Army of Northern Virginia.

On the morning of May 19th, Confederate General Ewell used his entire division for a flanking movement to determine the disposition of the Union Army. Shortly after 3:30 pm Ewell’s column, some 6,000 men strong emerged from the woods that had concealed their approach. Confederate skirmishers quickly came upon pickets of the Fourth New York Heavy Artillery. The Confederates troops soon realized that if they could push through the small picket line of the Fourth New York they could capture a large Union supply train parked nearby. While this tenuous situation was developing along the line of the Fourth New York, the First Maine Heavy Artillery had been relaxing in the woods off the Fredericksburg Pike. About 4:00 pm on the 19th the echo of musket fire could be heard coming from the direction of the Harris Farm and the Union supply wagons. At almost the same moment that the men of the First Maine realized what was happening their Colonel Daniel Chaplin received orders to take his regiment toward the sound of the action. The First Maine Heavy Artillery along with the First Massachusetts Heavy Artillery moved off quickly towards the sound of the growing battle. Portions of the Confederate advance had driven off the wagon drivers and the Confederate troops were beginning to rummage the unguarded provisions and supplies. After driving the Confederate raiders off and securing the supply wagons, the First Maine Heavy Artillery turned toward the still advancing column of the Confederate main line. The First Main Heavy Artillery along with the Fourth New York Heavy Artillery, First Massachusetts Heavy Artillery, First Maryland Infantry formed lines at Harris Farm and stood in battle formation prepared to meet the Confederate advance. Also supporting the Union effort were the Second and Seventh New York Heavy Artillery regiments. After a few quick advances by Ewell’s command that were checked by a determined Union defense, the engagement was closed with a fierce three to four hour stand-up fight at close range that lasted until night descended on the battlefield and Ewell decided to withdraw. The effects of the engagement and the standup fight were tremendous and devastating for both sides.

As the bullets from Ewell’s command slammed into the ranks of the First Maine Heavy Artillery, scores and scores of Maine men fell. For these men, most of whom had never been in combat before, the sights and sounds of battle were as indescribable as they were destructive. This first battle for the First Maine Heavy Artillery brought with it a large number of casualties. The regiment lost 155 to death or mortal wounds and another 375 wounded. Company D, which was at the end of the First Maine line guarding the right flank found itself positioned in a small wooded area. This small amount of cover provided protection, and company D only lost one man, Corporal Charles W. Smith an 18 year old from Bangor. The cries of pain from loved comrades wounded or dying, the rattle of musketry, the sound of leaden missiles tearing through trees, and the dull thud of bullets that found their human marks, produced a feeling of horror among those who survived the battle.

After resting most of the day on May 20, those of the First Maine Heavy Artillery who could still march were ordered to fall in with the rest of Tyler’s Heavy Artillery Brigade and join the march of the Second Corps at Massaponx Church on towards Milford Station Virginia. At Milford Station they were ordered into line and instructed to prepare breast works for an expected assault. Company D under the command of Lt. Henry Sellers was ordered forward to the main line to serve as pickets and warn of impending assault. The First Maine subsequently participated in the assaults and capture of key Confederate positions at Chesterfield Bridge on the North side of the North Anna River and served on the North Anna line from May 20th to the night of the 26th, extending the line along the North side of the river to east of the Telegraph road.

On May 24, 1864, the Heavy Artillery Brigade of General Robert O. Tyler was broken up with most of the heavy artillery regiments ordered to join other veteran brigades within Second Corps. Most of these brigades after three long years of battle were smaller than the heavy artillery regiments that were joining them. The First Maine was ordered to join General Price’s Brigade of the Third Division of the Second Army Corps. Three days later, the First Maine was ordered to join General Greshom Mott’s Brigade of the Third Division. By noon on May 27th the First Maine Heavy Artillery was again on the march with the rest of the Union Army Second Corps in the direction of Hanover Court House and further south. The column finally marched into line facing the Confederates near the small village of Cold Harbor on the Morning of June 2, 1864.

The First Maine and the brigade they were attached to did not participate directly but served in a supporting role during the Union offensive at Cold Harbor from June 2nd to the 12th. At Cold Harbor, on more than one occasion, Heavy Artillery regiments were selected to lead the assaults against the Confederate lines. The logic behind this was simple. Getting these larger, fresh regiments to lead the way would hopefully be more successful and would give the Union Army an opportunity to take advantage of any breakthroughs gained by these regiments by following them up with veteran troops. During the period from June 1st to the 12th the Army of the Potomac’s estimated losses were as follows: killed and wounded 10,971, missing 1,816 for a total of 12,787. The Union Army Second Corps, to which the First Maine was attached, took the brunt of Grant’s Cold Harbor offensive. Of the 26,900 soldiers present for duty the Second Corps had 494 men killed, 2442 wounded and 574 missing, for a total of 3510 casualties at Cold Harbor.

On the night of June 12th the Union Army resumed its move south. This time instead of moving directly on Richmond, General Grant’s plan was to capture the rail depot that kept Richmond supplied from all points in the South. The target was Petersburg, the convergence point of five major southern railroads that did their best to keep the Confederate capital and Confederate Army protecting them, supplied. The First Maine Heavy Artillery, along with the rest of the Third Division of the Second Corps crossed the James River on June 14th. On the morning of the 15th the order was received for the First Maine Heavy Artillery to march on towards Petersburg. By noon the march had started and by the late afternoon the First Maine began to arrive in the vicinity of the City of Petersburg. By June 16th the First Maine Heavy Artillery was in force in front of the O.P. Hare’s House and the hill it sat on. By late afternoon the First Maine was heavily engaged. In the late afternoon of June 18th after the outer defenses of Petersburg had been overrun during the previous 3 days of fighting, the First Maine Heavy Artillery was formed up to charge 300 yards across an open field and assault the fortified Confederate positions facing them at Hare House Hill.

During the three days prior to June 18th the fortified confederate positions at Petersburg were being bolstered by General Lee’s veterans of the Army of Northern Virginia. The Union Army could hear the troop trains rolling into Petersburg.

In looking at the troops under his command, General Mott recalled that he knew the chances for success in charging the Confederate works were slim and that the veterans under his command would not be willing to try again. Mott wrote: “I knew that it was useless to expect suicide in mass from my old troops, who had seen the wolf and felt his teeth and bore his scars”. Mott further explained that all he could hope was that a Heavy Artillery Regiment, like the First Maine “innocent of the danger it was to endure, would lead off with a dash, carry the works with a rush and then it was my duty to take care that old steady regiments were on hand ready to support, press and profit by any advantages won by the gallant forlorn hope.”

In the late afternoon of June 18th, 1864 the First Maine Heavy Artillery was ordered to assault the heavily defended confederate positions. The First Maine lead the charge and in less than 10 minutes 242 men were killed or mortally wounded, 372 men were wounded for a total of 614 casualties of a force of 950 men. Add the casualties of June 18 to the 594 casualties suffered by the First Maine Heavy Artillery before the regiment arrived at Petersburg and one quickly gets a sense of the savage nature of General Grant’s Overland Campaign during the spring of 1864. As a result of this attempted frontal assault the First Maine Heavy Artillery would earn the distinction of having suffered the highest number of battle casualties of a Union regiment during a single action during the war.

Although ordered to support the charge of the First Maine Heavy Artillery, the entire command of the First Massachusetts Heavy Artillery and the Sixteenth Massachusetts laid down instead of advancing. According to an official report when Major Cooper of the Seventh New Jersey ordered his regiment forward he quickly realized that he was not being properly supported and therefore did not move his regiment beyond the Hare house. Apparently the officers of these regiments also saw the hopelessness of the charge.

Upon hearing that the assault of the First Maine Heavy Artillery had failed, General Mead wrote to General Birney, “we have done all that is possible for men to do.” As a result, the Union Army prepared to lay siege to the city of Petersburg. The June 18th charge of the First Maine Heavy Artillery was the last assault made by Union forces during the opening days of the Petersburg Campaign..

The majority of the veterans of the First Maine Heavy Artillery who chose to record the regiment’s history decided not to focus on the controversial aspects of the June 18th charge and instead became comfortable with looking upon the charge as the culmination of their patriotic duty. Participation in the charge was a badge of honor and the mark of a true veteran. Those who missed out on what was to that point, and would remain the most significant experience for the regiment could not fully share in the brotherhood of the “gallant 900”.

In 1905 the survivors of the regiment erected a memorial to honor their sacrifice and those of their fallen comrades. This monument is the only memorial on the field at Harris Farm, and the only tangible reminder of what happened on that piece of Virginia countryside.

June 18th, 1864 was not the end of the war for the First Maine. They participated in General Grant’s Overland Campaign until Lee’s Surrender at Appomattox Courthouse. The following table illustrates the engagements the First Maine Heavy Artillery Regiment participated in following the June 18th charge.

While regiments on both sides of the conflict suffered from the rigors of war, no regiment seemed to suffer as badly as the First Maine Heavy Artillery. In only10 months of active field service from May 1864 to April of 1865 the First Maine Heavy Artillery earned the distinction of having suffered one of the highest percentages of battle casualties of any Union regiment during the entire war. In these 10 short months the First Maine Heavy Artillery led all Union regiments with the greatest number of battle deaths with 423 (23 officers and 400 enlisted men killed and mortally wounded, 260 died of disease, etc.)

The original members were mustered out on June 6, 1865. The remainder of the regiment including the accessions from the 17th and 19th Maine infantry remained in service and were mustered out at Washington D. C. on the 11th of September 1865.

Source of information for Regimental History: “The First Maine Heavy Artillery During the Overland Campaign” by Andrew J. MacIsaac, A Thesis in the Field of History for the Degree of Master of Liberal Arts in Extension Studies, Harvard University May 2001.

Soldier History

SOLDIER

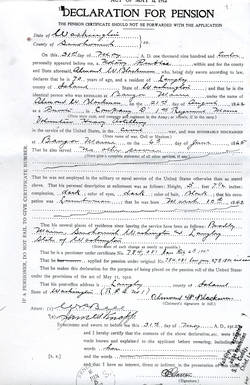

Residence: Eddington, ME Age: 20 years.

Enlisted on: August 21, 1862 Rank: Pvt.

Family History

PERSONAL/FAMILY HISTORY:

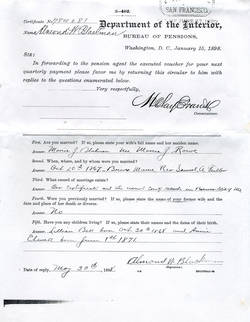

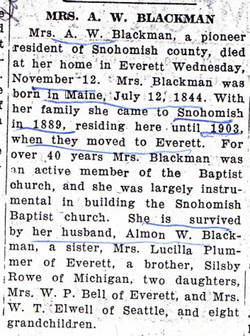

Almon W. Blackman was born March 10, 1842 in Eddington Maine. Having survived the war, he was married on October 20, 1867 in Brewer Maine to Marcia Jane Rowe. Almon and Marcia had two daughters Lillian A. and Annie M.

Almon, his wife and two daughters relocated to Snohomish County Washington approximately 1889. They settled in the city of Snohomish and resided in Washington for the remainder of their lives. Almon’s oldest daughter Lillian married Walter P. Bell who had moved to Washington in 1879. Mr. Bell served as the first city attorney for the city of Snohomish, and later was elected Attorney General for the State of Washington in 1908. Almon’s younger daughter Annie marred Will T. Elwell. The Elwell’s were an early pioneering family in the Snohomish river valley.

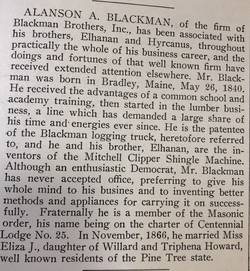

Almon Blackman was a first cousin to the well known and prominent Blackman brothers of Snohomish (Alanson, Elhanan and Hyrcanus). These brothers were some of the earliest pioneers in the area, Hyrcanus being the first mayor for the city of Snohomish. The Blackman brothers were leaders and innovators in the logging and milling industries in Western Washington.

Almon’s older brother was Charles A. Blackman who founded the C. A. Blackman mill. This was one of the earliest cedar shingle mills in Everett and was located at the far north end of that town site, an area then referred to as Blackman’s Point (now referred to as Preston Point). Almon and Charles had been financially involved in business in Bay City Michigan prior to settling in Washington and Almon was to some degree involved with his brother Charles in the C.A. Blackman mill at Blackman’s Point in the 1890’s.

In 1906 Almon took up a homestead of 160 acres in section 9 just to the west of Langley on Whidbey Island. Almon and Marcia lived on Whidbey Island for 6 years, later relocating to north Everett.

Almon Blackman was a member of the G.A.R. John Buford Post # 89 of Everett and he died at his home in Everett, at 1030 Rucker Avenue on October 4, 1920. His wife Marcia Jane died November 12, 1919. They were both laid to rest in lot 80, block 22, fourth addition of Evergreen Cemetery in Everett Washington.

(This family history provided by great great grandson of Almon Blackman, Edward Hartley Anderson, Mukilteo Washington, November, 2001)

Cemetery

Buried at Evergreen Cemetery in Everett

Adopt-a-Vet Sponsor

Edward Hartley Anderson

Mukilteo , WA